A Time Buffer is not the same as Total Float

Who owns the float has been a predominant discussion within project controls for decades. And it still is. However, to correctly address this question, the difference between Total Float and Time Contingency (or a time buffer) needs to be fully understood. We hope this blog post will help in clarifying the differences.

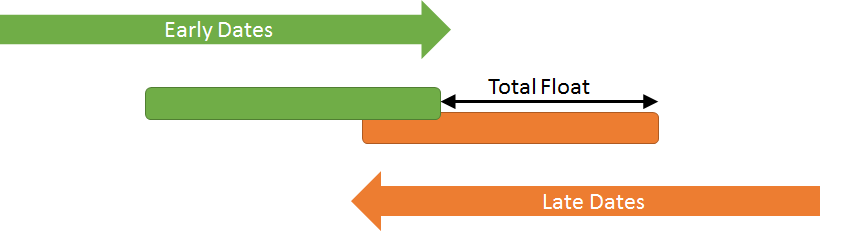

Total Float

Total Float is nothing else than the difference between the Early Finish Date and the Late Finish Date (or Early and Late Start) of an activity as calculated by the Critical Path Method.

It is a scheduling thing. It denotes how much an activity can slip without impacting some constraints, and often more relevant, any contractual milestone restricted by such constraint. Total Float shows that there is some sort of abundance in the planning. The time that is realistically estimated to complete a group of activities is smaller than the time allowed in the contract to complete them. This total float can be consumed without severe consequences for the project. But what if two contractual parties have suffered delays and both want to use the total float to mitigate them? Then the ownership question arises. We will come back to this later in this post.

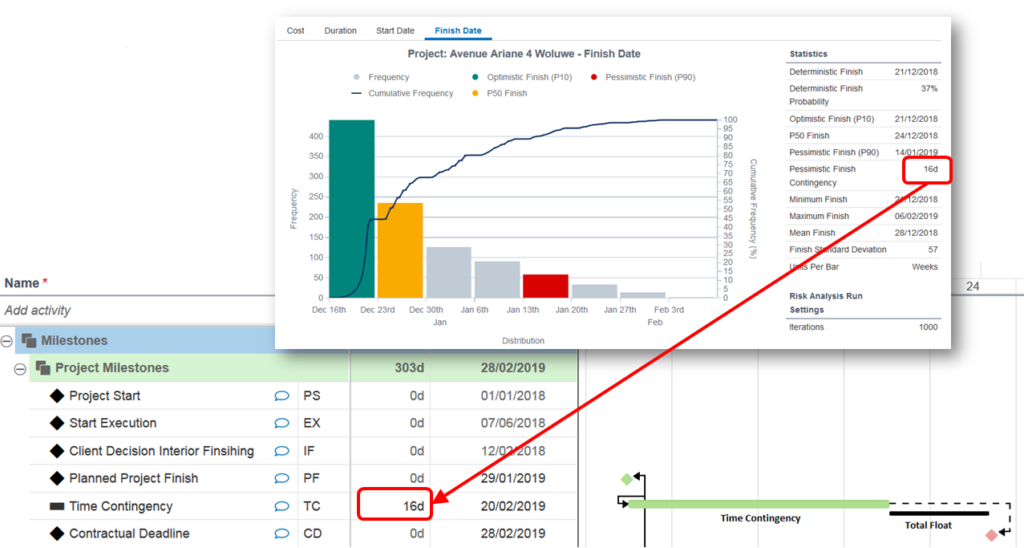

Time Buffers

A time buffer is something completely different. It is a contingency reserve added to the schedule to cope with existing risks and uncertainties. Mostly contingency reserves are added in front of major milestones to protect these milestones. This is the reasoning behind a project owner requesting its contractors to show that deadlines are met with a probability of at least 80%. The size of the required time buffer to obtain this kind of robustness should always be calculated based on underlying risks and uncertainties. Running a schedule risk analysis is the most correct way of calculating it. The required time contingency is then for example calculated as the difference between the P80 finish date of a contractual milestone and its finish date in the deterministic schedule. The resulting time buffer can then be added to the baseline schedule as an activity after the last activity to be completed before the milestone. After that, a risk-adjusted schedule can be calculated by re-applying the critical path method. Total float will be updated and will probably be reduced for the key milestones.

But, who owns the float?

The entire conversation on who owns the float results from the fact that it is often unclear who has ownership of the time abundance. The answer is complex and depends on the type of delay, the quality of project administration, the contract and even the applicable law. It might for example be the case that Total Float can be consumed on a First Serve First Come basis. Whatever the rule is, strange anomalies may occur and specialized project controls techniques will be required.

What should, however, be much more clear and is the main message of this blog post is who owns the buffer. The owner of the buffer is the party that owns the underlying risks and uncertainties. If I anticipate my risks in the schedule by including a contingency reserve, it is my buffer. It cannot be utilized by my contractual counterpart to cover up his delays.

That should be the rule, but once again one should be careful. Therefore, I would like to conclude this post with some important rules on adding time buffers to a schedule:

- Adding time buffers cannot be regarded as an excuse to turn all Total Float into buffers. We have seen ridiculously large time contingencies before. A means should be found (by the project owner) to prohibit this from happening.

- Any buffer should be based on realistic risks that are identified, quantified, analyzed and even mitigated. A clear distinction should be made between owner and contractor risks. All risks that a contractor uses to calculate a contingency reserve should be approved by the owner. Risk management should be a joined process.

- Make sure that buffers are added correctly into the project network. They should not only buffer the critical path leading to a milestone, but also other paths.

- A complex part of working with buffers is the control of buffers during execution. As the number of open risk decrease throughout the project, so should the size of the contingency reserve. We will write in later blog posts about this topic.

Conclusion

Total Float and buffer are sometimes used as interchangeable concept, but they are not. They are calculated differently and have completely different contractual implications.